Columbia Business Magazine

Social Impact

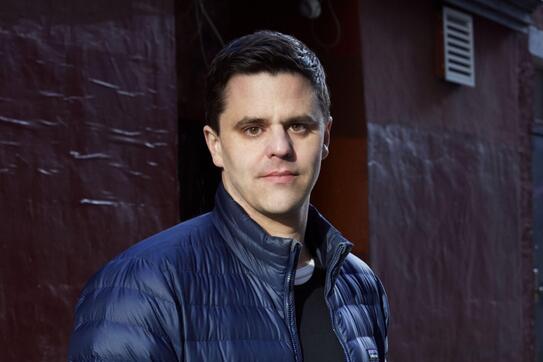

Despite concerns about Europe’s energy stability this winter and beyond following Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, Columbia Business School climate economist Gernot Wagner sees signs of a “green industrial revolution” finally underway in the West. The stakes of the climate debate are shifting, he notes — though he adds we’d be forgiven for failing to fully notice it given the stream of grim headlines.

In the following conversation, Wagner, a native of Austria, describes how a transatlantic divergence on climate recently became a clean-energy race, why European leaders missed an opportunity in their response to Putin’s invasion back in February, and why he’s hopeful about the green industrial policies finally taking shape in the United States and elsewhere.

CBS: Do you think Russia’s invasion of Ukraine could hasten the West’s transition to cleaner energy?

Gernot Wagner: Yes, I do. And my answer would have been very different if we’d had this conversation before August.

Between February 24, when Russia invaded Ukraine, and July, it had become increasingly obvious that the United States and Europe were taking two completely different paths. Europe as a whole, and most of its individual countries, used it to do some of the things that everyone knows are necessary for both national security and the climate. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine sped up the energy transition in Europe.

Whereas in the United States — and again, this is a pre-Inflation Reduction Act view of the world — very little of that happened. The United States is more isolated, more insulated from what happens in Ukraine. Only about 10 percent of our imported oil came from Russia and basically none of our gas. Biden declaring an oil and gas import ban is much easier to do than, let’s say, the Germans doing it. So there was no plan to double down on energy transition domestically. If anything, it was the opposite. It was basically, let’s build more liquefied natural gas terminals; let’s pump more. That difference even showed up in stock market prices. European clean-energy companies performed better right after the invasion; US ones didn’t.

Fast-forward to after the signing ceremony for the Inflation Reduction Act and the transatlantic divergence has become a clean-energy race that the United States has finally entered.

As of December, it seems both the United States and Europe believe they’re in this together and want to use the current gas energy crisis as a reason to transition and do what is necessary — fast.

CBS: Some environmentalists fear that the fast-action solutions Europe has taken to shore up its energy supply could cement dirty energy systems in place. For instance, European countries are devising the short-term fix of floating terminals to receive liquefied natural gas from other countries, especially the United States. Do you share this concern that Europe may not be doing enough to go the clean-energy route?

Wagner: I’m much less concerned about what happens in any given year than about the trends, about bending the curve. The COVID lockdowns in April and May 2020 cut emissions; Europe running coal plants longer increases them. Neither has much of an impact long term. What matters is how what we do affects the trajectory. Does building that gas terminal lock us into yet more gas for longer, or might it be used for green hydrogen someday soon?

Overall, of course, a lot more is needed. It’s so late in the clean-energy race. This is not Eliud Kipchoge figuring out how to break his own marathon world record. This is us playing catch-up, all the way from the back.

And yes, there were many missed opportunities along the way. Imagine if on February 25, the day after the invasion, when everyone was shell-shocked, European leaders didn’t just ask for us to defend democracy but actually suggested real steps? French President Macron, say, could have said, “We are asking all French, Germans, Europeans who can to work from home starting Monday morning. We are not heating our offices, nobody is driving to work, and we will take the savings and half will be donated to Ukraine and the other half will be spent on building insulation and heat pumps.”

But those emergency measures didn’t happen for months. That’s a huge missed opportunity. Beginning over the summer, in anticipation of a cold winter, we did see calls for people to conserve. That should have happened the day after Putin’s assault on Ukraine. And now that we are in the crisis, the conundrum is we have to provide relief for those not able to afford their energy bills without creating adverse incentives. You do not want to lower prices at the margin and encourage more demand. In the end, the best cure for high energy prices is high energy prices.

As an economist, what you want to do then is lump-sum transfer funds back to households. That’s hard to implement politically, when people see the high gas bills. I don’t envy any politician facing this right now. They’re going from fire to fire, from crisis to crisis. And yes, the key is to use this crisis as an opportunity to say there are some things we could and should do and to try to make things better.

CBS: Given that the behavioral and policy changes that we know need to happen have proved so elusive, is it a question of whether countries, and especially the West, can mobilize to meet these types of challenges if we’re not already facing a crisis?

Wagner: Change is hard. We are in a situation where we know that we need to change our ways, stop with the status quo of privatizing profits while socializing costs left and right. We know we need to change policies; we need to be better at pricing risk, internalizing externalities.

This progress happens in fits and spurts, but we are indeed making progress. We’re making progress on security issues in Europe. We’re making progress on clean energy. But finding the right balance is really, really hard substantively, and it’s even harder politically.

CBS: Do you see any reasons for optimism?

Wagner: What makes me hopeful is that business is indeed seizing the opportunity. Yes, it takes policy, and with the passage of the US Inflation Reduction Act, the passage of the CHIPS Act, and the passage of the bipartisan infrastructure bill, we are pivoting, and pivoting fast, toward green industrial policy in this country. Europe has been doing it for quite a while longer, and China and other countries too are engaged in this push.

Then look at business engaging in all sorts of other ways. After moving from a policy to a business school this past summer, I didn’t expect to once again attend a United Nations climate meeting. But yes, Columbia Business School had a significant presence at COP27 in Egypt this past November, hosting panels on financing the transition to net zero and the skills and resources future climate leaders will need to create measurable change in their communities.

Ultimately, of course, it is the interplay of policy harnessing private interests and channeling market forces in the right direction that will make the real difference. We’re at the very beginning of this global clean-energy race. Success is not guaranteed, and not everyone will be an economic winner. But we’re looking at hundreds of billions of public investment dollars leveraging trillions of dollars worth of private investments. That’s an exciting opportunity if there ever was one.