“Is there a fish there or not? If you see him, how do you get him to come up? Of course, the beautiful part is, once you catch him, you release him so you can do it again.”

When Robert F. Smith ’94, founder, chairman, and CEO of Vista Equity Partners, is on the phone, which seems like almost every free minute of the day, he is constantly moving, pacing, and searching out the unexplored corners of the room like a bloodhound following a trail. Rather than the restlessness of a distractible person, this is a relentless search for newness, value, and meaning. By and large, Smith has found value in the people and places that are most often ignored.

The son of two teachers (both of whom held PhDs), Smith had the background to become an academic, and to this day his interests run wide and deep, and conversations with him often take a turn toward the philosophical.

When Smith started at Columbia Business School, after earning several patents as a chemical engineer, he never intended to go into finance (he had originally enrolled in Columbia’s joint JD/MBA program, but he fell out of love with the legal profession after a summer spent “with the lawyers at Philip Morris”). He didn’t think he liked finance, but after more than 100 conversations and interviews with people in the industry, he decided that the only business he really enjoyed was mergers and acquisitions. “With the exception of warfare, [M&A] is how assets are transferred on this planet,” Smith says.

Shortly after graduation and some prompting by John Utendahl ’82, now the vice chairman at Deutsche Bank Americas, Smith was working for Goldman Sachs. He chose Goldman, he says, for its teamwork-oriented, learning-based culture. Smith became Goldman’s first M&A banker in the newly emergent tech epicenter, Silicon Valley, and he oversaw mergers and acquisitions at tech giants like Apple, Microsoft, Texas Instruments, eBay, Hewlett Packard, and Yahoo! Inc.

“At that time, technology for us [Goldman Sachs] was the defense companies—Northrop Grumman and General Dynamics and Lockheed Martin—a little company we took public called Microsoft, and another little company called IBM, right?” Smith explains. “We had a few folks out on the left coast who were competing, but mainly in the corporate finance business, the IPO business. We didn’t have anyone on the ground focused on technology as an M&A banker in San Francisco.”

For many, being one of the first investment bankers to wade into the steaming morass of Silicon Valley in the 1990s would have been the high point of a career, but Smith was just getting started. The tech bubble burst in 2000 as companies with sky-high valuations but poor execution went bankrupt. But for Smith, tech was still golden.

While working for Goldman in San Francisco, Smith advised companies like Apple, “where we kicked out the board and invited Steve Jobs to rejoin the company.” Apple, of course, went on to become the most valuable company in the world.

Rather than being lured in by the siren call of dot-coms, Smith saw an opportunity in enterprise software companies, and in 2000 he launched Vista Equity Partners. Smith created Vista with the goal of unlocking the nascent value of enterprise software companies by using a “Six Sigma,” or “systematic,” approach. “These software companies were truly value plays, from my perspective,” Smith explains. But only “if you actually knew how to change the operations of those businesses.”

Smith credits his Columbia education, in part, with the success of Vista’s model of buying and then investing heavily in often-overlooked enterprise software companies. “You think about Warren Buffett and Henry Kravis, and to a great extent, Columbia seems to mint a whole bunch of people who understand value investing and go about it in a different way,” he says.

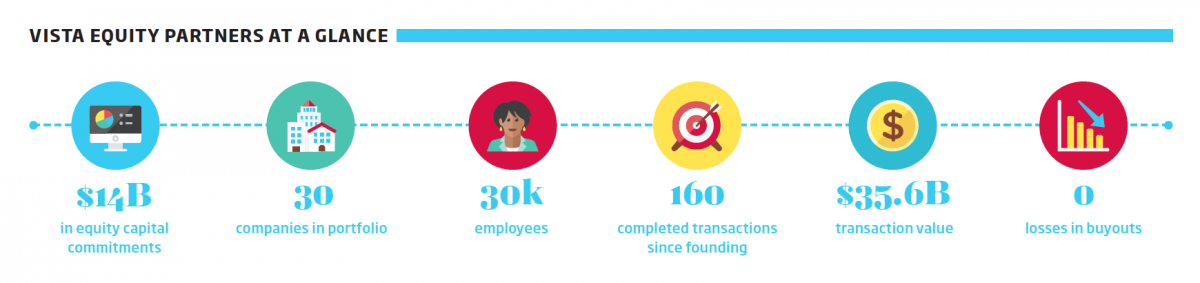

Vista now manages over $14 billion in equity capital commitments with a portfolio of more than 30 companies, which employ over 30,000 people. Since its foundation, Vista has overseen more than 160 completed transactions, representing over $35.6 billion in transaction value. The company has had zero losses in buyouts and has consistently performed in the upper echelons of private equity firms worldwide.

Transformational Impact

Staying in tech wasn’t the only way that Smith followed his own path. Whereas the standard operating procedure for private equity firms is to purchase struggling companies and cut costs until they can return them to profitability — or load them up with cheap debt before shutting them down in the worst scenarios — Vista focuses on building highly profitable companies by investing in them. “We exclusively focus on enterprise software and are re-facing private equity from being transactional to being patient and transformational,” Smith says. “We also believe that we have built a model of private equity for scale and longevity based on our people, processes, and infrastructure.”

In practice, this means that Vista invests heavily in tried-and-true processes, and, most importantly, focuses on hiring top-notch, hungry talent. Smith looks at new portfolio companies and new talent in the same way: as value investments, a familiar concept for any graduate of Columbia Business School. Potential employees who may not have had access to the same opportunities as more conventional hires are good investments — they work hard, are exceedingly loyal, and are driven to perform above and beyond expectations. Likewise, Smith looks for enterprise software companies that have good fundamentals but are perhaps weak in their execution.

When Vista acquires a company, it immediately begins implementing a series of Vista Standard Operating Procedures — “VSOPs” in the firm’s lingo. “We have applied VSOPs again and again successfully in software companies, no matter what sector they are in — from energy to healthcare,” Smith says. “We capture what we have learned and transfer skills and know-how to our companies and, through a systemic approach, leverage our investment team, Vista Consulting Group, and our portfolio managers.”

Vista also imbues each company with a meritocratic approach to human resources, which may be Smith’s greatest achievement.

“I understood at an early age the importance of excelling and merit-based rewards,” Smith says. “I often remind my children of the three words that resonated with me in my early years, in college, at Goldman Sachs, and when I made the decision to go out on my own: you are enough.” Smith says this deceptively simple phrase has guided him “and countless others to reach our own, and in fact our collective, potential.”

In practice, Smith’s philosophy is an unusual amalgamation of laissez-faire survival of the fittest and a progressive desire to open up opportunities for the disadvantaged in the world. In essence it means that anyone, if their talents are correctly identified and they are given the right opportunities, can achieve what they want in life.

Vista Equity Partners forces its companies to incorporate this philosophy into their corporate practices. The company uses a finely tuned aptitude test—the origins of which date back decades to a questionnaire originally developed by IBM—to “assess technical and social skills and problem-solving abilities and determine fit within specific job functions at a software company,” Smith explains.

Vista only hires people who score well on the test but also takes into account their emotional intelligence quotient and leadership abilities. The aptitude test allows Vista to identify potential employees who have the capacity to be highly successful. This means that a stunning résumé or a degree from an Ivy League institution is less valuable in the hiring process than a high score on the test.

In one instance, Vista hired an ex-archaeologist based on her test score, and she went on to manage 50 people after only 18 months on the job. “We have taken a former roofer and converted him into one of our best software salesmen. We took a Domino’s Pizza manager, gave her a boot camp training experience, and now she leads the training for the whole company,” Smith says. In another case, a shelf stocker at Walmart blew the top off the test and was offered a job in Vista’s systems group. Vista gave him a salary 28 percent higher than what he originally asked for.

“He went back to Florida where he lived, packed up his wife and his cat, and drove,” Smith recalled. “Showed up on Monday. He lives across the street now from the headquarters organization. I’ll guarantee you 10 years from now he’ll still be working for us.”

In another instance, a mailroom employee at MicroEdge — a Vista portfolio company — took the test, scored highly, and was moved into a quality assurance role. Four years later, he is now reporting directly to the company’s chief technology officer. “He’s the second most senior person in our software development organization. Probably is going to be a rock star as a CTO in a Vista company some day,” Kristin Nimsger, CEO of MicroEdge, said during a recent Columbia Business School panel.

“We look for people with the drive to succeed, and then we promote them,” Smith says. The meritocratic nature of Vista’s hiring process is what makes the company successful and its platform scalable, according to Smith. “I want the smartest people on the planet. If you look at our Vista companies, they come in all shapes and forms. They come from different schools. The fact of the matter is, they didn’t get into Ivy League schools. Not all of them have that opportunity,” Smith explained during a recent panel at Columbia Business School.

If you train people “and you give them that opportunity to really transform their lives, they’re appreciative,” says Smith. “And it actually helps stabilize the communities in which they live, which is where your companies exist, and it cultivates that whole meritocracy element. Part of what we should do, if we are successful people, is provide opportunities for other people and our economy. This just comes from living in a community. And a community can be your family, your neighborhood, the city, the state, the country you live in. You do have an obligation, in my mind, to provide an opportunity for people to use whatever skills and talent that they have or even desire.”

Smith cultivates this meritocratic, team-based corporate culture at Vista and its portfolio companies, and as part of that he encourages all of his employees, managers, and business units to practice what he calls the “life-boat test.” This is as simple and efficient a test as the process of natural selection, and it is designed to help people identify strengths and weaknesses in their teams.

he encourages all of his employees, managers, and business units to practice what he calls the “life-boat test.” This is as simple and efficient a test as the process of natural selection, and it is designed to help people identify strengths and weaknesses in their teams.

“Here’s how this works: our ship goes down. We’re all in a life boat, and we’ve got 11 people on it.” When Smith explains the lifeboat test, he pauses dramatically at this point. “Who’s the first one you throw overboard? Who’s the second? Who’s the third?” The lifeboat is meant to be analogous to the fact that for a company to survive and thrive, everyone must be trying to exceed the expectations of their peers.

Deep, Broad Focus

Smith has said that although leading Vista is his dream job, in another universe he could have been in public service. “I enjoy what I call the process of collaborative solutions and coming up with elegant solutions to complex problems,” he says.

In 2010, Smith founded Project Realize, which enables Vista to strengthen and “adopt” companies that are committed to serving their communities. Vista supplies an “executive on loan” to help implement some of its VSOPs within each adopted company. “Business should create real, sustainable value,” Smith says. “I believe that business is uniquely able to find solutions that deliver social good and profits at the same time — that is our mandate.”

In his own career, as one of the few African Americans at the top of the rarified world of private equity, he feels that at times he had to work harder to gain people’s respect. The challenges Smith has faced over the years may influence why he seems to be constantly wrestling with enormous philanthropic and civic urges. Smith sits on the board of Carnegie Hall, is the chairman of the Robert F. Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights, and is a trustee of the Boys and Girls Clubs of San Francisco. He is a member of the Leadership Circle for the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial in Washington, DC.

Smith says that while it would be “wonderful” to believe that government and philanthropy will help “level the playing field in terms of educational opportunity,” a “person who is born in North Carolina, who doesn’t have access to a great school in a rural county . . . should have access to great opportunities if they are smart and they really want to work hard.” And nobody works harder than Smith.

But when he does take a break, Smith likes to fly fish. “Fly fishing gives you a chance to actually get out and commune with nature,” he says. “One of the things that people don’t do enough of is think — actually just think. We’re all so busy. Even now, you and I are on the phone, but of course, I’ve got e-mails coming in and Blackberries buzzing and iPhones ringing, and so we end up in this reactionary-type environment every day.”

Fly fishing helps Smith become “more mindful, more thoughtful,” he says. “It makes you slow down and actually focus. You have to focus on everything that you’re doing, seconds at a time.”

When he talks about fishing, you can almost hear Smith’s thoughts matching pace with the river. He references Norman Maclean, the author of A River Runs Through It, when trying to explain why he fly fishes. “I think it’s those times when clarity comes, when you have a chance to kind of calm your mind and calm your spirit so you can actually think deeply about the problems you’re facing and how to solve them.”

Smith encourages his executives at Vista to think in this way and recommends that they each take half a day every week “to stay home and just think,” although he warns that this does not mean staying home to do “your honey-do list or anything of that sort.” This kind of deliberate thinking helps create sustainable solutions to business problems, he says.

Yet Smith fishes for another reason as well — simply to become a part of nature. “You’re standing in the water, and you have the water flowing around you. If you think about it, all life on this planet comes from water, and now you’re kind of connected to that water. You’re standing in it. Your feet are on the ground. You feel it rushing around your legs, and over time, you just become fully connected and grounded and centered in that whole experience. “I find that to be quite euphoric,” Smith adds. “It takes you to a place and transports your mind and transports your body in such a way that things become a little better focused.”