On a sunny day in Santa Monica, Gibson Pierre ’19 pushed his three-month-old daughter in her stroller while walking by the beach with his wife, Robyn Price Pierre (’19GSAS), and their Yorkshire Terrier. The day, for Gibson, was nothing memorable: just one of many spent enjoying a walk with his family. For Robyn, though, it held a moment of revelation. She couldn’t help but notice the big smiles, craned necks, and extra attention from each passersby. While used to observing averted gazes when they walked as a couple without their daughter, this onslaught of new attention struck Robyn as odd.

Later that day, unable to forget the smiles that had followed her family on their walk, Robyn realized that people were reacting to what they believed was a rarity worthy of acknowledgement: a Black man, with his family, being a committed father.

“It was almost like the stroller was what humanized him to people, what made him accessible to people,” says Robyn. “Just as the suit he wears to work makes him accessible, or his MBA makes him accessible. He has to put on these layers that make him more human to someone else. And that bothered me.”

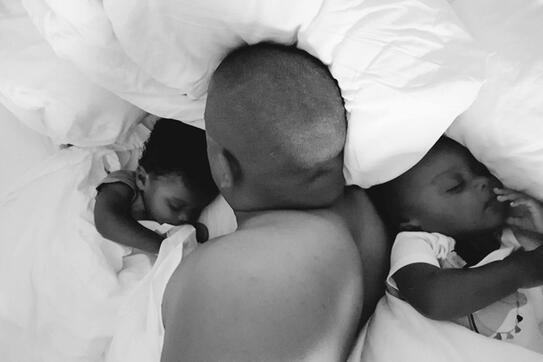

The experience was the catalyst for Fathers, a photo book that compiles personal photos from families depicting simple moments between fathers and their children. The photos offer a glimpse into the universal experience of fatherhood, but through the lens of Black men, who are seldom represented in mainstream media as fathers.

“There is such a lack of these types of images in newspapers, in fashion magazines — everywhere,” says Robyn. “If people were to open a time capsule and look back at the representation of Black people through the lens of media, what would they really know about us? I imagine they’d see these odd, nefarious caricatures of Black life. So I started to see this as an archival project — collecting images of Black life from the people who lived it.”

While the need for the book itself was clear to the Pierres, the route to getting it published was one filled with obstacles. “For us, it was really about the product,” says Robyn, who served as editor and creative director for the book. “We started a publishing company out of a necessity to bypass the traditional gatekeepers. People spend years trying to convince a large company that something matters. We created it out of a need to tell a story and make sure we weren’t turned away.”

Gibson, who was pursuing his MBA at the Business School at the same time the two began work on the book, shifted his focus from his longtime interest in real estate finance to learn more about the publishing industry. The result of his work was Twenty Eight Ink, the company that published Fathers, where he serves as VP of business development.

“We walked into the publishing space with no knowledge,” says Gibson. “Robyn took on the bulk of the work beginning to understand the nuances of the publishing industry, and I later took a class at the Business School where I studied a larger publishing company to learn what drove its revenue and how it handled its operations.”

Learning as they went, the pair created both a publishing company and a book from scratch, the final product being a 400-page art book brimming with images sourced from calls put out to personal networks. The images are taken on camera phones; by family members and partners; and depict honest, intimate moments of fatherhood.

“In terms of a coffee table book, nothing like this existed, at least that we were aware of,” says Gibson. “The images in the book show men who are vulnerable. They are loving. They bleed the same as everyone else.”

On choosing a medium, Robyn notes that it was important to allow the fathers in the book to tell their stories themselves and choose photos that felt meaningful to their experiences, as men are often not asked to expose their more emotional, vulnerable sides.

The intimate images resonated with many, including Gibson’s CBS classmate Brianna Lowndes ’19, chief marketing officer at the Whitney Museum of American Art, who made Fathers available for sale in the Whitney’s bookstore. “Bri is really an example of someone who is an ally and who is doing the work,” says Robyn. “She saw the book and she championed it, she was a gatekeeper and she used her resources and access to open the door.”

The book serves as a tangible step toward introducing more nuanced images of Black men into mainstream media — a step that is vital not only to a more accurate representation of America’s population but also to protecting lives.

“When Gibson would go running in Central Park after our daughter was born, I felt a fear I’d never felt before,” says Robyn. “I knew that if he was out running and anything happened — if a Black man was being searched for nearby — that he would fit their profile, any profile. They wouldn’t know that he was a man with a daughter at home whom he’d just put to sleep. They wouldn’t immediately associate those human characteristics with him.”

Fathers is a collection of simple moments, housed in a coffee table book, but it is also a societal imperative.

“When you look at these images, you are entering people’s lives, even if it’s just a glimpse,” says Gibson. “It’s a work of art. And I think it should be in everyone’s home. I’d think we’d see less Amy Cooper birdwatching incidents if Black life and Black bodies were normalized. The world can’t continue to be centered around one skin color.”

Twenty Eight Ink recently published The First Pair, a photo book about sneaker culture that answers the question, “What was the first pair of sneakers that made you feel fly?”