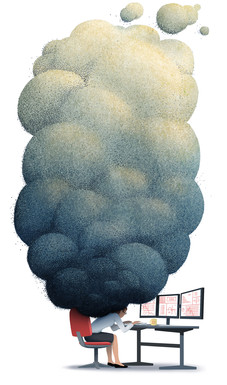

The health impacts of air pollution are well known. When we breathe bad air, we’re likely to suffer sore throats and have difficulty breathing. Certain chemicals in the air can even hinder our cognitive abilities. All of this has been shown to lower worker productivity—and not just for manual laborers in the smog-plagued developing world but also for white-collar workers.

The health impacts of air pollution are well known. When we breathe bad air, we’re likely to suffer sore throats and have difficulty breathing. Certain chemicals in the air can even hinder our cognitive abilities. All of this has been shown to lower worker productivity—and not just for manual laborers in the smog-plagued developing world but also for white-collar workers.

A new study by professors at Columbia Business School and Leibniz Universität Hannover shows that even relatively small amounts of pollution can impact the productivity of white-collar workers. Looking at trading by individual investors in Germany, the study finds that even a one-standard-deviation increase in particulate-matter (PM) pollution—an amount so small most people would be unable to discern it—makes investors 8.5 percent less likely to log on to their online brokerage accounts and carry out trades.

“Even though the pollution is just a little bit worse, it has a big impact,” says co-author Michaela Pagel, the Roderick H. Cushman Associate Professor of Business at Columbia Business School. “I was kind of shocked by that.”

The findings reflect data collected from one of Germany’s largest brokerage firms, as well as from 600 air, traffic, and weather stations located across the country. In designing their statistical models, the authors were careful to control for several factors that are closely correlated with pollution but are also likely to affect trading on their own. One of these is traffic: gridlock adds to PM pollution but also often lengthens commutes, leaving people with less time and inclination to trade. Another factor is rainfall, which washes pollution out of the air but may also lead people to stay indoors and trade more.

Since sitting down at a computer to actively manage your portfolio requires some degree of intellectual exertion, the authors use willingness to trade as a proxy for white-collar productivity, which means its effects could be far-reaching. “To the extent you think these people’s willingness to sit down and trade is the same as my willingness or ability to do research,” says Pagel “then the findings are important for all of us.”

The 8.5 percent drop in productivity due to pollution is the same percentage change observed in response to a one-standard-deviation increase in sunshine, which typically has a significant impact. “When the sun is shining, everybody is outside; nobody sits home in front of their computer, especially in Germany,” says Pagel.

Michaela Pagel is the Roderick H. Cushman Associate Professor of Business in the Finance Division of Columbia Business School.

Though Pagel was surprised by the magnitude of the results, she expected the overall findings would link upticks in air pollution to decreased productivity. Pagel lives in New York City, and she got the idea for the study after repeatedly cleaning black dirt out of her air conditioner and experiencing some of the symptoms associated with PM pollution.

The pollution creates a “type of brain fog,” says Pagel. “The fine particulate matter goes through people’s noses into their brains, which makes them feel less sharp and less able to engage in a cognitively demanding task like trading or other office work.”

Pagel says she experienced this herself. “I was waking up oftentimes with a little bit of a sore throat. I totally think the feeling translates into an impact on high-brain work.”

Pagel suspects that many office workers in the developed world go through their days without realizing the toll pollution is taking. Many of the related papers that preceded Pagel’s focus on people doing physically demanding labor in countries with much higher pollution levels.

“To my knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate the negative impact of pollution on white-collar productivity at the individual level in a Western country,” says Pagel.

Drawing again on her own experience, she adds, “If I lived in a less polluted place than New York, I would probably be a tad more productive in the high-brain work that I’m doing.”

The results show that PM pollution has the most pronounced effect on people who trade frequently. This further supports the idea that willingness to trade can be used as a stand-in for productivity. “If you trade a lot—as opposed to, for instance, every six months—that makes it closer to white-collar work,” Pagel says. “It’s more like a daily activity.”

In addition to lowering productivity, PM pollution might also hurt worker performance. Not only are those who log on to their accounts on smoggy days less likely to make a trade, but the trades they make are also less valuable. Pagel admits these results aren’t as conclusive, since there’s a selection bias that comes with looking only at people who choose to log on to their accounts on polluted days, as opposed to the entire sample of investors. But it’s another reason employers might want to pay attention.

“For businesses, if you take these findings seriously, it may be a smart idea to invest in something like an air cleaner,” says Pagel, who swears by the air purifier she picked up for her apartment.

“For policy more generally, we want to encourage people to use alternative means of transportation,” Pagel explains. “You also want to try to have less air conditioning and fewer cars, which are big sources of pollution. Those are the main takeaways.”

ABOUT THE RESEARCHER

Michaela Pagel

Michaela Pagel is the Roderick H. Cushman Associate Professor of Business at Columbia Business School. She received her Ph.D. from the Economics...