How a mathematician and sports analytics expert transformed the game of golf.

In the world of golf, Mark Broadie is an unlikely celebrity. He is not a professional athlete. Professor Broadie is a mathematician and expert in sports analytics who designed what’s known as the strokes gained method, a way of measuring a golfer’s performance that has transformed the world of sports statistics and, in many cases, the game itself.

Detailed in his 2014 book, Every Shot Counts, strokes gained uses historical data to compare a golfer’s rounds to those of other players based on the start and end point of each player’s shot. The measurement represents a great equalizer; before it was adopted by the PGA Tour in 2011, golf statistics couldn’t differentiate between a player who sank a putt from 3 feet away, and one who made it from 20 feet. This allows players to assess their strengths and weaknesses relative to their opponents’, and provides greater context for fans and analysts to each golfer’s game.

“It’s become part of the lingua franca of the sport,” explains Ken Lovell, senior vice president of ShotLink Business Operations and Golf Technology for the PGA Tour.

A New Jersey native, Broadie began golfing as a teenager, and played sporadically following a move to New York City in the 1980s. After joining an area golf club in the early 1990s, he played more frequently and began to think about how to combine his passion for the game with his data-driven academic pursuits.

In the last decade, Broadie’s system has done for golf what the development of sabermetrics has done for baseball—offered new ways to analyze and interpret an old game. Hardly a tournament broadcast goes by without a commentator mentioning the stat, and earlier this year, the Golf Channel called the creation of strokes gained one of the top 25 most impactful moments of the last 25 years.

A Game Changer

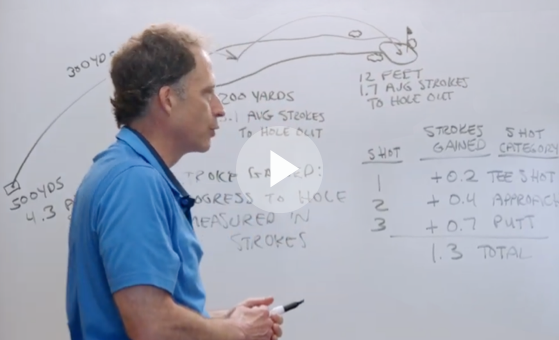

Mark Broadie explains the strokes gained method that has transformed the way we analyze and play the game of golf.

Broadie says that since developing strokes gained, golf stars such as Rory McIlroy, Luke Donald, and Justin Thomas have reached out to him about how they base their practice sessions on knowing what their strokes gained number is on a certain course.

“I’ve heard some very nice quotes from players and coaches that they use strokes gained all of the time,” he says.

As it’s relatively easy to socially distance while playing a round, both the professional game and the golf industry have seen gains in popularity since the onset of the pandemic. Lovell notes that television ratings for the PGA Tour have been up since tournaments resumed on June 11, and that there has been an uptick in golf equipment sales.

He adds that statistics such as strokes gained enhance the experience of the game for fans.

“They are a way to show and to entertain people at a deeper level than just putting a picture in front of them,” Lovell says.

Below, Broadie, the Carson Family Professor of Business, whose classes include Business Analytics and Sports Analytics, explains how strokes gained transformed golf and how this method may be adapted for other aspects of business. He also discusses the exponential growth of analytics in sports, and chronicles his lifetime love of golf.

What is the story behind the creation of strokes gained?

I wanted to combine my personal interest in golf with my professional interest in analytics.

I realized that the analytics work I was doing at Columbia Business School would have ideas that could answer what I thought would be interesting questions in golf. One of them would be explaining where the difference comes from, between a golfer whose average score is 90, versus a golfer who typically shoots 80. Where did those 10 strokes come from?

To answer that question, you need shots. I looked around to see if I could get shot-level data looking at how far a golfer whose average score is 90 hits the ball compared to how far an 80 golfer hits the ball, plus see how many times they landed in the fairway. There wasn’t any information on that. So, I created a program to gather shot-level data for amateurs.

In the 80 versus 90 golfer example: If you figure out how good and how poor each shot is relative to a benchmark, the value of all shots will add up to the 10-stroke difference over the round. Then you can see how much putting, driving, and other parts of the game contributed to that 10-stroke difference.

How did the PGA Tour become involved?

In 2003, around the same time I was assembling my data, the PGA Tour started collecting shot-level data for professionals, but they would not give it to me. They said, “It’s too expensive, we’re just not going to give it way for free.” The tour used laser technology to track where every shot starts and where every shot finishes. Then in 2008, they wanted to improve their putting stats. They came to me and said, “You’ve been doing this stuff with strokes gained, can we adapt this for use on the PGA Tour?” So they agreed to share their data.

There’s a lot of luck involved in these things. You can have a great idea and there’s no data. You can also have the data and an idea, but nobody is interested in it. I had a method that I had developed and the PGA Tour had a need.

Did you always feel that golf statistics needed to be updated?

The statistics that were in use in the early 2000s were the same ones that were in use in the 1950s. If you go back to pre-computer days, you can count things: How many putts? How many fairways did you hit? How many greens did you hit? With the collection of shot tracking data the PGA Tour created hundreds of new stats, but it was too much information and too little insight. They presented all of this stuff that people couldn’t make heads or tails of. So initially, they didn’t want strokes gained to be the 351st stat that was just lost in the shuffle.

Ken Lovell, Senior Vice President of ShotLink Business Operations and Golf Technology for the PGA Tour:

It allowed instructors to talk about things with players in a way they hadn’t before. Before coaches would say generally “it’s approach shots that are killing you.” Now, they could point out that if you would have done two shots better in your approaches, you would have won the golf tournament.

Anna Rawson ’15, former LPGA professional golfer:

It’s interesting to know where you compare to the rest of the tour. Knowing where you are in comparison to everyone else is always helpful, and statistics are very good for TV commentators and people watching to compare players.

Patrick Goss, Director of Golf, Northwestern University:

We use strokes gained in everything we do. We’re able to say to players, “You improved eight-tenths of a shot from last year. You’ve got another 1.4 shots to go to get to where you want to be.” Strokes gained was really the first time we were given the pieces of the puzzle. It helped us focus practice with some strategy.

How did strokes gained become accepted as an insightful statistic by the PGA and the golf world at large?

The PGA Tour went to thought leaders, influencers, key writers, players, and coaches, and showed them two blind rankings of PGA Tour putters, one based on the old-school method and one based on the new strokes gained method. The PGA Tour asked which ranking was more accurate and, without knowing which method created which ranking, these thought leaders and others picked the ranking based on strokes gained. The PGA Tour got immediate buy-in without even having to explain the method, a strategy that I would never have thought of. It’s not enough to have a good idea, it has to be adopted. How they went about that was brilliant.

Has the strokes gained method changed the way you look at golf history?

The shot-tracking data that measures where shots started and ended has only existed on the PGA Tour since 2004. However, you can get some historical insights and perspectives by applying the strokes gained system to the scoring data that is available. One player could shoot a 72 and another could shoot a 69, but if they are at different courses, the 72 could represent a better performance than the 69. One way to place those two performances on a similar scale is to compare each score to the average score of the field at that course. So, if a player shoots a 69 and the average is 71.4, the player is said to have beaten the field. The strokes gained value is simply the difference between those two numbers, or +2.4 strokes in this case. That means the 69 was 2.4 strokes better than the field average. Every player in every round either “beats the field” or doesn’t.

I’m curious about records in golf, so I wondered who had the longest streak of consecutive rounds beating the field. I went back to 1983, which is when scoring data on all the players in a field started to be compiled, and asked a number of people in the golf world who they thought owned the record for the longest beat-the-field streak. Most guessed correctly—Tiger Woods. But then I asked them about the length of the streak, and most guessed between 20 and 30. The real answer is astounding. At one stretch in his career, Tiger Woods beat the field 89 rounds in a row. For some context, the next closest is Mark O’Meara at 33. It’s comparable to Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak in 1941, which is considered the ultimate in sports statistics.

What are some of the most drastic changes you’ve seen in sports due to data and analytics, and what does the future hold for the use of data in sports?

In many sports, analytics is still growing because of the availability of new data, especially through player tracking. In basketball, the NBA tracks the positions of all the players on the court and the ball 25 times a second. There’s even more interesting analysis that could be coming. Imagine a golfer who’s wearing a fitness tracker. Now you could measure the pressure they feel by their heart rate. Putting a player’s biometric information together with the action on the course or field makes for some fascinating possibilities.