Some of the steel industry’s most prominent and experienced leaders are at the forefront among those sounding the alarm about their industry: its emissions have more than doubled since 2000, and it must decarbonize significantly — and fast.

Kyung-sik Kim, a longtime senior executive at Korean steelmaker Hyundai Steel, was among the nine global steel experts who recently visited the CBS campus to collectively tackle the urgent question of how best to do just that.

“To see the future of steel, we need to look to the past,” noted Kim, who is now retired from his post at Hyundai Steel and heads South Korea’s Steel Scrap Center. Societies have been making and relying on steel for millennia, he said, and the Industrial Revolution supercharged steel’s usage. Engineering technologies have continuously improved ever since, but there has been one constant throughout: coal, which, mixed with iron ore, produces copious amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2).

“What will happen in the future?” asked Kim, who is also a former committee member of the Second National Master Plan for Energy and a former expert committee member of the National Climate and Environmental Council. “There is one variable that is different from the past: It is carbon dioxide.”

As the world’s climate crisis grows and jurisdictions around the world roll out new climate policies — including direct carbon pricing systems like the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) targeting CO2 generated outside its borders — the deeply established steel industry will need to transform. And it will have closer to a decade, rather than a century or millennium, to do so this time.

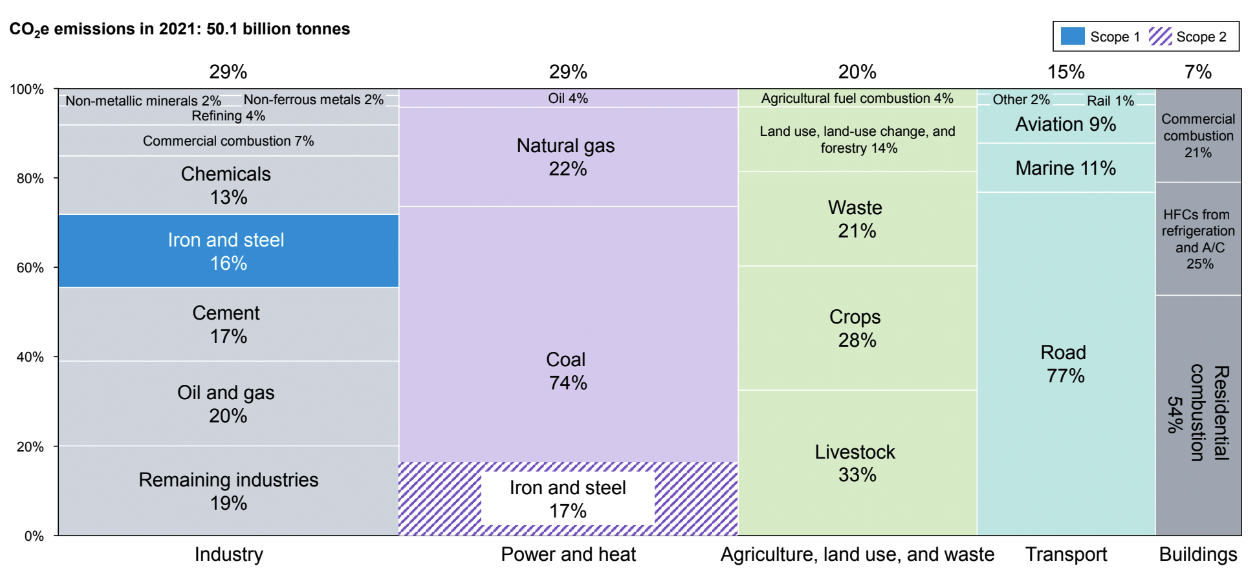

Together, manufacturing sectors account for over 30% of global annual CO2 emissions, and within that broad category, steel is among the top emitters (see graphic below). Though emissions from steelmaking have finally decoupled from production levels as of 2016, demand for steel is rising rapidly — especially in emerging economies. In the absence of major interventions, emissions from steel production will continue to increase.

To limit further temperature increases and forestall the worst effects of climate change, global CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions must reach net zero. To do so by 2050, iron and steel production must slash emissions by 25% as soon as 2030, according to the International Energy Agency.

The clock is running out. Such a deep and fundamental change to one of society’s most important forms of production ought to warrant decades or more of experimentation and innovation, but the world has waited until close to the final buzzer to act. Steel is considered one of the hardest to abate sectors for a reason: The elegant chemical process that transforms iron ore and coal into iron also happens to release large amounts of carbon dioxide, which is no longer tenable. Now is the moment to make up for lost time.

Click on the links below to read four key points shared at the steel decarbonization workshop:

Insight 3: The world needs a consensus definition of green steel (and green iron).

Insight 4: A just transition for steel should include resources for educational and training programs.

Read more about Columbia Business School’s Climate Knowledge Initiative