Adapted from “My boss is younger, less educated, and shorter tenured: When and why status (in)congruence influences promotion system justification,” by Huisi (Jessica) Li of the University of Washington; Xiaoyu (Christina) Wang of Tongji University; Michele Williams of Iowa University; Ya-Ru Chen of Cornell University; and Joel Brockner of Columbia Business School.

Key Takeaways:

- Workers with a boss they perceive as competent overcome the impression of unfairness prompted by status incongruence — defined as having a boss that’s younger, less educated, or less tenured than the worker.

- Workers with a less competent boss are more likely to look to status indicators like age, education, and tenure to justify the boss’s position. This is an example of system justification theory, whereby people attempt to reconcile the psychological discomfort of being in a flawed system by searching for ways to justify it.

- Employers looking to promote or hire employees with status incongruence should emphasize their competence in the role to avoid perceptions of unfairness; employees should try to be aware of their reactions to status incongruence — otherwise, they may fall prey to justifying an unfair system.

Why the research was done: Decades of research have shown the positive impact of high perceived fairness in the workplace on worker productivity and morale. CBS Professor Joel Brockner and his co-authors sought to examine some potential causes of perceived fairness, focusing on status incongruence — when an employee’s supervisor lacks traditional signifiers of higher status, such as being more advanced in age, education, or tenure at the company.

Status incongruence has been on the rise in the workplace for a while. The uptick in bosses younger than their subordinates could have to do with the growing tech industry, which is dominated by young workers, as well as the aging workforce. “Many people are working longer,” says Brockner, the Phillip Hettleman Professor of Business at Columbia Business School. “People who would have retired — and therefore been out of the workforce — stick around, so you have more older people in the workplace and more of a likelihood of status incongruence.”

How the research was done: To understand the workplace impact of status incongruence, the researchers looked beyond the impact of each status characteristic on its own. They examined the interplay of that variable with the perceived competence of the supervisor. Typically, the status indicators of age, education, and tenure lead to a perception of competence, but not always. “We were trying to do something different,” Brockner says. “Rather than asking, ‘How do status characteristics lead to perceptions of competence?’ we asked, ‘What if we separated these two factors and examined their joint effects on a worker’s perception of fairness?’”

For field data, the researchers used a collection of Chinese HR surveys that asked employees questions including how competent they thought their boss was at performing their job.

They also conducted laboratory experiments in which they asked US workers to consider various workplace scenarios — including an older versus younger boss and a more competent versus less competent boss —and asked them to respond to questions about the fairness of the organization’s promotion system. To process this data, the researchers performed statistical analyses, including an analysis of variants and multiple regressions.

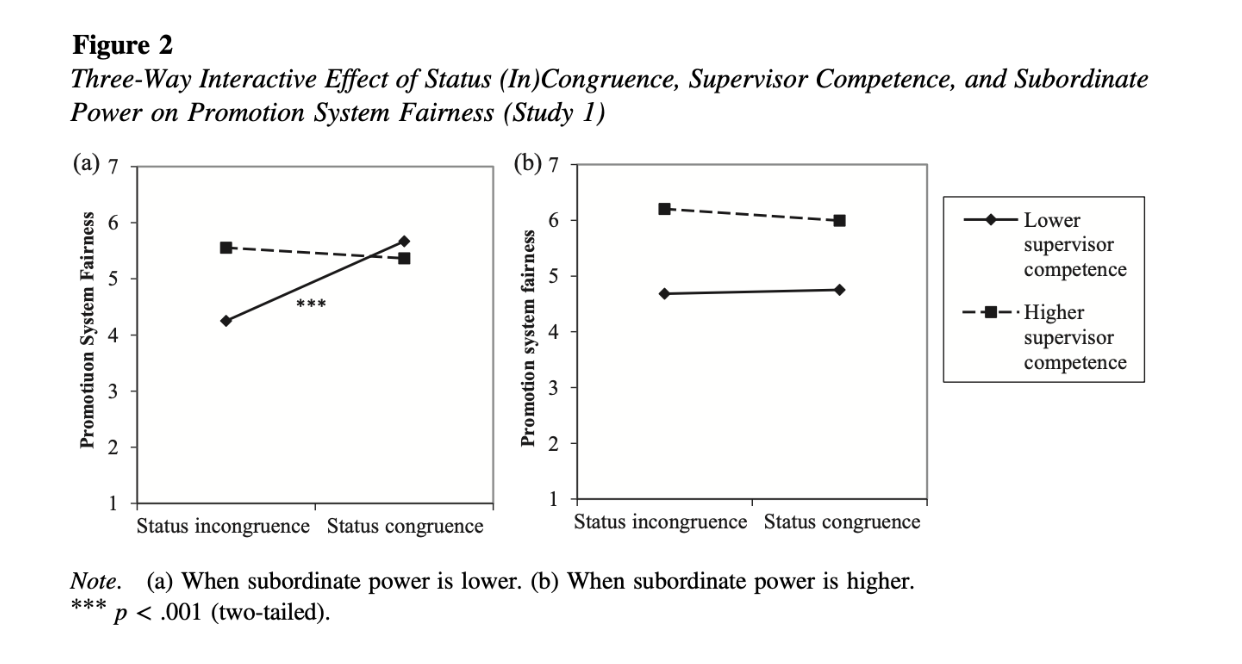

What the researchers found: If workers viewed their boss as competent, regardless of whether the boss was status incongruent, they perceived the promotion system in their workplace as fair. “The status characteristics didn't matter when people were seen as competent,” Brockner says. “Regardless of status congruence or incongruence, as long as the boss is seen as competent, then people will perceive the promotion system as fair.”

When a supervisor was considered less competent, however, status indicators had more of an effect on workers’ perception of fairness, as they looked for ways to explain the boss’s promotion. In these scenarios, “the more status characteristics a boss had, the fairer the promotion system was considered,” Brockner says.

The researchers believe the results they observed are rooted in system justification theory, which states that people want to see the systems they’re embedded in as fair and legitimate — and they will attempt to rationalize unfair elements of the system to the extent that they can. This effect was particularly pronounced in instances where workers had few alternatives for employment — in other words, they were pretty much stuck with their current positions. “If I have a boss who's not that competent, psychologically, that's kind of distressing to me,” Brockner says. “But if I have no escape, I better come to terms with it. I better make the best of that bad situation.”

Why it matters: As status incongruence becomes more prevalent, this paper offers practical implications for supervisors and workers. Higher-ups, knowing how status incongruence impacts workers, can be proactive about assuring employees that status-incongruent supervisors are competent and therefore were fairly promoted into their roles. Newly promoted young supervisors can take heart that if they show their competence in the role, subordinates are more likely to accept their status.

Finally, employees should be aware of their reactions to status incongruence, including the possibility that they will attempt to justify a flawed system while working under an incompetent boss to avoid the psychological discomfort of remaining in that flawed system. This can have long-term disadvantages, like causing a worker to stay in an unfair work environment. As the researchers note, “Acknowledging one’s system as unfair may be a trigger for psychological discomfort but can also be a catalyst for change.”